March 5, 2024

by Sjoerd Duiker

It’s frost-seeding time!

Frost seeding is an economical way to establish cover crops in winter in standing wheat or barley, or to supplement a thin forage stand. Although not as foolproof as drilling, it is a reasonably successful practice.

Here’s four tips that can help ensure success:

1. Be timely. The time for frost seeding is when the soil is going through freeze-thaw cycles. This causes a “honeycombing” of the soil surface that helps improve seed-to-soil contact.

Frost seeding works well on loamy and clay soils that hold water, but it is not suited for use on sandy or shaley soils that dry out quickly. The best time to perform frost seeding is early in the morning when the soil is frozen, and a thaw is expected during the day. This reduces the chance of soil compaction while providing the desired soil heaving that improves seed-to-soil contact.

2. Select the right seed. The best species for frost seeding generally are small-seeded, germinate quickly and grow well in cool conditions.

Red, white and sweet clover are the most successful species, while birdsfoot trefoil can also be used for pasture renovation despite slower germination and early growth.

And although yellow sweet clover can cause animal health problems because of coumarin content (a blood thinner), it is not likely to cause livestock health problems if it is only a percentage in pasture.

When seeding legumes, be sure to inoculate them with the appropriate rhizobium before broadcasting, so symbiosis will take place to fix nitrogen. In pastures, some non-fluffy grass species such as annual or perennial ryegrass may also be frost-seeded.

Do not mix grass and legume seed for broadcast application as the legume seeds will throw farther than the grass seeds because of their greater density, which leads to nonuniform seed distribution.

3. Be consistent. Make every attempt to guarantee uniform coverage by knowing the width of spread and spacing between passes.

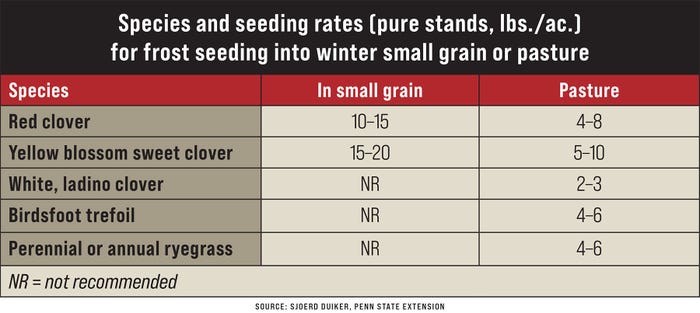

Recommended species and seeding rates are below. Seeding rates in small grains are higher because no repeat application is possible. With pasture renovation, frost seeding complements an already established stand and can be repeated next year if not successful. Heavier seeding rates for pasture renovation would be used in thinner stands.

It is common to mix clovers for pasture renovation. Red and ladino white clover make a good combination. This is where you use twice the seeding rate of red clover compared to white clover (for example, 2 pounds an acre red, plus 1 pound an acre white clover up to 6 pounds an acre red, plus 3 pounds an acre white clover).

4. Let animals do the work. Frost seeding for pasture renovation will likely be most successful in pastures with bare spots or those that are overgrazed.

Besides relying on the freeze-thaw action at seeding, you can also use grazing animals to tramp in the seed shortly after broadcasting. This practice may be especially helpful for improving seed-to-soil contact if a thick thatch layer that would compromise frost-seeding success is present.

However, don't turn out animals in wet conditions as this can cause soil compaction.

If you miss the best “window” for frost seeding, clover seed will remain viable in the soil, and much of it will likely grow when the conditions are right. If you notice your stand is not adequate in summer, you can selectively no-till legumes or grasses in late summer to fill in thin spots to resolve any lingering issues.

Here are other useful web resources:

Duiker is a professor of soil management and applied soil physics at Penn State.

Read more about:

BarleyYou May Also Like