September 22, 2023

The other day, I decided the time was right to start clipping a few meadows where the weeds had gotten ahead of the grass. I had my batwing cutter stored at another farm, so I drove down there and hooked it to the big tractor.

Knowing the blades would need to be sharpened before trying to mow down thick growths of pigweed and goat weed, I brought it back to the home place and parked it beside my shop building. With the wings of the cutter folded in an upright position, I plugged in the right-angle grinder and began to sharpen the first of six dull blades. They were so blunt, they wouldn’t even beat a weed to death.

Work smarter

Before I even had the first blade sharpened, the strain of the heavy grinder was causing an all-too-familiar back pain. Looking around to make sure I was out of sight from anyone traveling down the road (I wouldn’t want any neighbors to think I was too old to perform a simple bit of work), I retrieved a metal folding chair from the shop and proceeded to sit down while I sharpened the blades.

That eased the pain significantly, allowing me to take my time and spend the next hour putting on the best edge these blades had seen since they were new.

Once I had the blades sharpened to my satisfaction, I was eager to get started on an 80-acre field north of the house — and then I remembered that I needed to grease all the fittings on the cutter.

For those who don’t have a 15-foot batwing cutter, you should know that there are about 1,000 grease zerks to service on a daily basis. Actually, there are 38 — it just seems like 1,000.

To access all the grease points, I lowered the wings of the cutter. This would allow me to manually rotate the drive shaft and expose each of the myriad of zerks. But to my surprise, the drive shaft would not rotate. The harder I tried to turn it, the more noise it made.

Diagnosing the problem

Slowly, I walked around the machine, contemplating what could possibly be preventing the movement of the drive shaft. As I pondered, I figured I had just as well test each of the six tires for proper inflation, so grabbing a hammer from the toolbox, I thumped each one. They all seemed fine, as evidenced by a healthy bounce, but since I had the hammer in hand, why not hit the gearbox with a little love tap? Maybe that would cure whatever was causing the problem. It did not.

Growing more frustrated and angrier by the second, I rationalized that starting the tractor engine and ... just barely ... nudging the PTO control knob, I might be able to break loose whatever was impeding the drive shaft from moving.

However, I decided to first engage the hydraulics and raise the entire mower. Underneath the 3-ton machine, to my surprise and embarrassment, was the crumpled remnant of a metal folding chair.

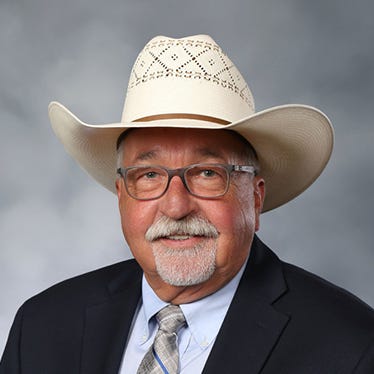

Crownover raises beef cattle in Missouri.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like