Nearly a month after the deadly collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge and the subsequent closure of the Port of Baltimore, there is hope that ships carrying agricultural products could be on the move soon.

Government officials are hoping to open a limited-access channel by the end of the month that would support one-way traffic barges and roll-on and roll-off farm equipment. The port is the largest export point for ag equipment in the U.S.

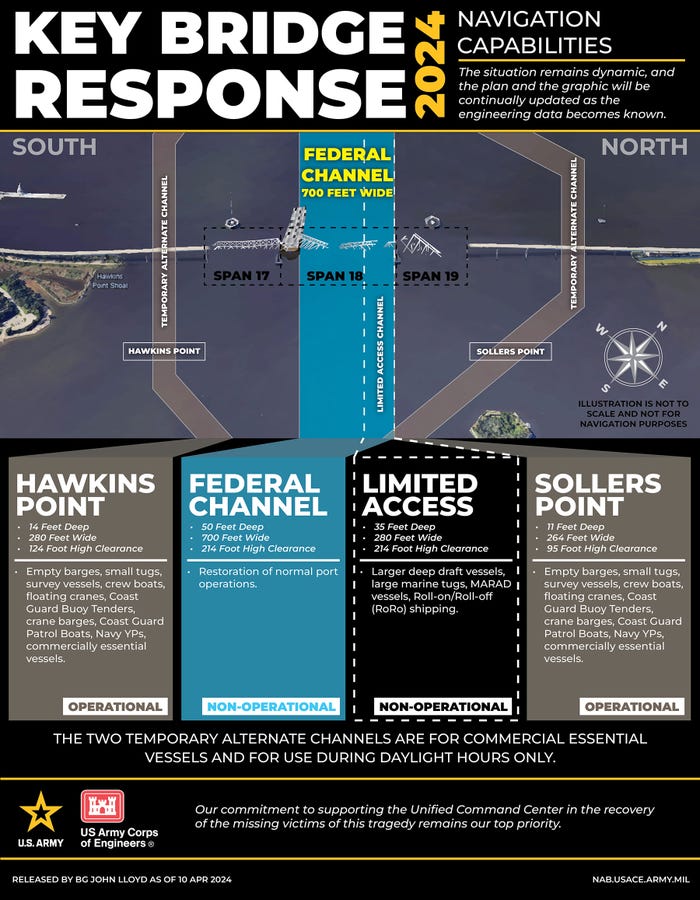

Thus far, three temporary channels underneath the remaining portions of the collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge have opened:

One channel has a depth of 11 feet, a 264-foot horizontal clearance and a 95-foot vertical clearance.

The second channel has a depth of 14 feet, a 280-foot horizontal clearance and a 124-foot vertical clearance.

The third channel has a depth of 20 feet, a 300-foot horizontal clearance and a 135-foot vertical clearance.

Kevin Atticks, secretary of agriculture, says the Army Corps of Engineers’ goal is to open a 35-foot-deep channel by the end of this month, and then a permanent 50-foot-deep, 700-foot-wide channel by the end of May, which would essentially reopen the port to full traffic.

But he also warned that nothing is guaranteed given the complexities of the site cleanup.

“It’s easy to underestimate the complexity of moving the wreckage from the bottom,” Atticks says. “There are parts of the bridge deep in the mud, wreckage, pavement down there. And we’re sensitive to the fact that there are still souls in the water.”

The impact of the port’s closure on agriculture has been significant, he says. Farmers and cooperatives who have decided to divert exports to other ports are facing significantly higher costs.

There have been concerns about fertilizer supply and inventory given the fact that companies such as Yara and Meherrin have major terminals at the port and haven’t been able to get shipments in.

“What I’m hearing from local purveyors and suppliers is that they’ve got enough right now, but if those stocks aren’t resupplied, it will have to come from somewhere else, and that could be more costly,” Atticks says.

He adds that financial relief for businesses directly affected by the port closure is also being considered.

That could be welcome news for Lippy Brothers Farms of Hampstead, Md. The farm ships soybeans from its own farm — which produces 200,000 bushels of soybeans a year — and from 150 other farms across the region. Last year, the farm shipped 3.7 million soybean bushels out of the Port of Baltimore, says Tyler Rill, the farm’s export manager.

Rill says the farm had 155 containers full of soybeans on the Dali, the ship that crashed into the bridge late last month, and another 100 containers waiting to get on other ships bound for Southeast Asia.

Some containers have been moved to an inland port in Virginia where they have been staged for later shipment out of the nearby port in Norfolk. But this has added lots of costs, Rill says, which the farm is eating because they have already set contracts with farmers and end buyers.

“If we have to go to Norfolk, we are probably losing 95 cents a bushel,” he says. “It is 250 miles from Baltimore. And on average, we move probably 30,000 bushels a day. So, do the math.”

The farm has more than 1 million bushels of grain storage capacity, but the bins are full, Rill says, so there is no option of bringing the containers back. In the meantime, the farm’s end customers want their product.

“It’s been pretty rough. It just all stopped at once for us,” he says. “We had to basically shut our whole operation down. It’s been an interesting few weeks here to say the least.”

The farm has 8,000 acres of field crops, including corn, soybeans and wheat. The farm began exporting soybeans 17 years ago, but the past five years have seen impressive growth. “Some of it is through word of mouth, and some of it is just our relationships with farmers,” Rill says.

If the soybeans are moved and exports get going again, the farm will export wheat later this summer, something it has never done before. Still, Rill is concerned about the long-term impacts of the accident and hopes his customers will stick with him.

“Our customers that have beans with us right now and would typically come to us, maybe they will go somewhere else,” he says. “In terms of what we are planting, it is not affecting planting decisions, per say. But because of that, we’re probably going to lose some beans we could have potentially had.

“That port is such a big factor for a lot of different reasons. It’s going to get back and open, and running smoothly, but I hope it is soon.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like