Potato producer Bruce Barrett says pulling up a potato vine reminds him of opening a gift on Christmas morning. But he says the aerial, real-time imagery he’s receiving from Ceres Imaging is like looking in the closet to see the gift before it’s opened, yet still wanting to open it come Christmas day.

Barrett co-owns Springlake Potatoes, Springlake, Texas, with his brother, Steve. Together, they produce several varieties of red and yellow potatoes on 1,400 acres of sandy soil irrigated by more than 70 center pivot irrigation systems in Lamb and Bailey counties. They manage their soils with cover crops and crop rotation and also run cattle. And like most, the Barrett’s are looking for management tools to increase production efficiency.

“We’re trying to optimize our yield, but it’s not our main goal,” Bruce says. “It’s about what the market is, and what they [the markets] say we need, so we’re on a timetable. When you get to the end of July on reds [potatoes], the market is pretty much going to collapse.”

Bruce describes their Texas operation as a gap filler. “We work with a brokerage company out of Idaho and when the northern areas run out of potatoes but haven’t started the new crop, they’ll come to us and say, ‘We need you to take care of the Walmart business from the end of June until middle of August.’ And that’s what we’re doing, filling that gap.”

While the farmer nature of the Barrett brothers wants to produce more, bigger and better potatoes, Bruce says that’s not always what the market needs.

MANAGEMENT TOOL

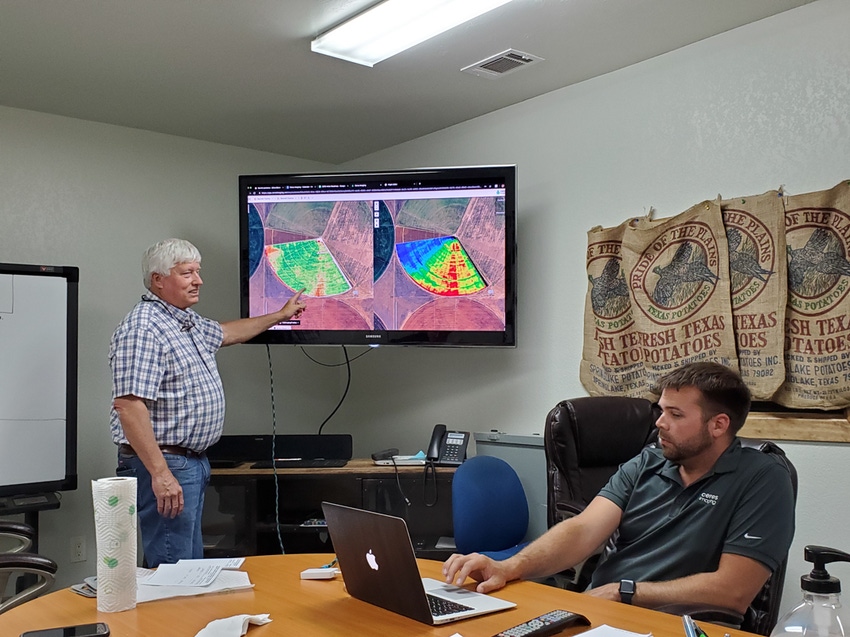

The Barrett’s have begun using data generated by Ceres Imaging to fine-tune production. Ceres, a California-based company founded by Texas-native and CEO Ash Madgavkar, generates high-resolution, multispectral imagery with five cameras and one thermal sensor mounted to a fixed-wing aircraft.

Ceres flew the most of the Barrett’s fields approximately six times during the growing season.

See Photo Gallery, Multispectral imagery: a tool in production management toolbox

“The iPad app they use configures the cameras,” says Jeff Divan, Ceres Imaging agronomy lead. “It tells them where to fly, how high and how fast to fly.

“They’ve learned how crops respond differently at different wavelengths when they’re under different stress and that’s why it’s different than a drone. A drone is a picture, but this is trying to model what is actually happening in the crop based on how the plants respond to the different wavelengths.”

Ceres’ layered images depict chlorophyll, water stress, thermal, color infrared and NDVI, an index used to measure vegetative growth. They also provide analytics for center pivots and specialty crops.

Springlake Potatoes farm manager Nate Barrett says he likes the Ceres technology because it overlays with their John Deere Greenstar operation center. “Keeping everything in one program is nice.” But he also likes how “The pictures show you what your eye doesn’t see.”

“We joke a lot that we are in the potato business not the potato vine business,” Steve says. “Yes, we want to know about the vines, but sometimes the best vine doesn’t always make the biggest potato.”

“There’s a lot going on at the same time in potato production,” Bruce adds, “and it’s figuring out how we can apply that (real-time data) to what we are doing.”

PESTS AND DISEASE

The Barrett’s hope the Ceres technology can help expose and identify pest and disease issues.

“Blight, when it starts spreading, will sometimes be on the edge of the field,” Bruce says. “Maybe we will be able to pick it up a little earlier, so we can spray earlier.”

The Barrett’s also hope for early detection of psyllids, an insect that devasted their potato crop from 2008 to 2011. “The problem with psyllids is once you start seeing symptoms, you’ve already been infected,” Bruce says.

Since the 70s, better varieties and chemistries are available to combat the insect, but Bruce says psyllids have built up immunity to some treatments. “It’s a constant fight,” he says.

To take it a step further, Tim Gonzales, Springlake Potatoes partner and farm manager, says he would like to see the images display coverage following fungicide and insecticide applications.

“We're doing a lot of flying with fungicides and insecticides, so we’d like to see our coverage, to see where the product is going, depending on the wind, and how much we are losing. Is it going on the crop or is it pulling off to the side? Am I doubling up?” Gonzales says.

“Fungicides cost a lot of money and because they’re systemics, you're looking at $80.00 an acre per spray. That's a lot of money to say, ‘Hey, we're just going to put it out there.’”

DRIFT

The Barrett’s also would like clarification on drift. “This is touchy right now, but last year we had a lot of drift,” Bruce says. “This year, we’ve had some. But we don’t know where it’s coming from.”

The potato farms are surrounded by cotton, corn and some sorghum fields. “We are ahead of everybody,” Steve says, “so when a lot of these guys are applying preplant, they don’t have anything out there, there’s dirt everywhere, whereas we’ve got a crop up and growing.”

Where drift comes from remains a mystery. “Last year, when we started seeing it, the crop duster flew a helicopter across and there wasn’t a pattern he could find,” Nate says.

“We did all kinds of stuff — drone, helicopter — but we couldn’t find rhyme or reason. Some guys were spraying around us, but it didn’t necessarily match,” Bruce adds.

On the red potatoes, 2,4-D drift, because it’s a growth hormone, splits the tuber and causes them to form an unmarketable shape, describes Bruce. “Instead of growing normal and elongated, they boomeranged, so we had a whole field near Muleshoe, we couldn’t even harvest.”

In the yellow potatoes, he says drift weakens the plant and makes it more susceptible to early blight. “The blight came quicker than normal.” Had they known about the blight sooner, Bruce says they could have sped up their fungicide program.

The problem, according to Steve, is they don’t know what the end result is of drift exposure. “We know paraquat is going to kill the plant or do this or that, but with dicamba or 2,4-D, there’s a lot of unknowns until we get the crop out.”

And while the Barrett’s admit they have a lot more questions than answers, they hope the Ceres’ technology can help them find some remedies.

A TOOL

In the meantime, Bruce, Steve and Nate admit they are still trying to learn how to interpret the data and incorporate it into their operation, while also finding time to go through all of the information. But Bruce says what may be valuable is what they gain over time.

“It will be interesting to see what it does and where it is after a year. You'll know this much, then after another year, you'll know this much. Those are things that take time to get there.”

They are not expecting technology to replace boots on the ground. “It’s another decision tool,” Steve says. “The images are confirmation of what we’re doing or if we are missing something, even though we are driving by the fields all the time. We’re not trying to eliminate going out and looking; we’re still going to do that.

“I think with most technologies you don’t know how you are going to use them for a while. We might end up using this in a way we don’t anticipate.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like