April 22, 2024

Cool-season grasses, such as tall fescue, orchardgrass and Kentucky bluegrass, are widely used across the U.S. for grazing and hay.

Cool-season grasses are highly productive and resistant to different weather conditions and provide adequate nutrition for cattle. However, being cool-season grasses, they struggle to grow during the warmer months of summer, resulting in a summer slump.

In the past couple of years, native warm-season grasses (NSWG), which thrive in warmer temperatures, have been explored as an adequate alternative to cool-season grasses during the summer slump.

However, a few challenges have been identified for growing NWSG. NWSG quality has been questioned, as previous research showed higher fiber and lignin contents and lower crude protein and digestibility.

Some people believe NWSG are “rough,” can grow in any environment and, therefore, do not need fertilization. In fact, decreased NWSG yields have been associated with high N fertilization levels.

On the other hand, others support that if NWSG are frequently grazed at medium utilization levels (50%), cattle will consume primarily leaves, which are high in quality. In this case, however, N fertilization would be helpful, if not essential, to sustain regrowth.

Grass production with AMF

One downside of fertilization and frequent grazing is the potential negative effects on beneficial soil microorganisms such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. AMF are an important component of grassland ecosystems, forming mutualistic associations with the roots of many grass species. These fungi play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and plant growth, enhancing plant access to nutrients such as P and N.

Studies suggest grasses colonized by AMF have increased root biomass, improved drought tolerance, and resistance to soilborne pathogens. Moreover, AMF have been found to influence the composition and diversity of grassland plant communities by altering competitive interactions between plant species.

The positive effects of AMF on grass growth and ecosystem function highlight their importance in grassland ecology and management. The effects of grazing frequency on AMF’s relationship with cool- and warm-season grasses remain underexplored.

Grass species, AMF and grazing frequency

In a recent study implemented at Ohio State University, we quantified colonization rates of AMF in three NWSG species (switchgrass, big bluestem and Indiangrass), three cool-season grasses species (tall fescue, orchardgrass and Kentucky bluegrass) and one legume (white clover).

All species were cultivated in a greenhouse for nine months under different cutting frequencies to simulate different grazing strategies. Cutting frequencies were based on leaf availability in the upper, grazeable stratum (upper 50% of the plant).

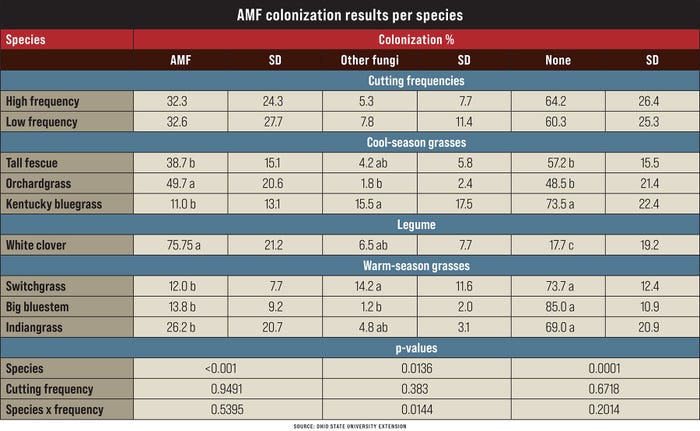

Since cool- and warm-season grasses and legumes grow at different rates, the cutting frequency varied between species. Findings indicate that cutting frequency did not affect AMF colonization. We also measured colonization by different fungi (endophytes) and quantified when no colonization as observed.

On average, a lower cutting frequency was cut every 26 days, resulting in an AMF colonization of 32%. Higher cutting frequency was cut every 17 days, resulting in an AMF colonization of 32%.

However, we did observe effects of different species on AMF colonization. White clover had the highest amount of AMF colonization with 76%, followed by orchardgrass with 50%. In comparison, the lowest amount of AMF colonization was switchgrass, 12%, and Kentucky bluegrass, 11%.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and endophyte are fungi found on roots, and no fungi found were measured in this experiment as a percentage. Table 1 describes all the colonization levels within the cool-season grasses, legumes and native warm-season grass plant roots. The lowercase letters show differences among species.

There was no effect of cutting frequencies on AMF colonization. White clover had the highest colonization rate, along with orchardgrass. The standard deviation of means was high across all values, which is common in biological processes.

The results indicate that cutting frequency does not alter the amount of AMF colonization within the roots of plants. All species were also able to form an interaction with AMF. Still, the level of interaction or colonization within the roots of the different species varies under a similar management practice.

Recommendations

A crucial agent for grass growth is AMF, and associations can happen in various forage types, including native warm-season grasses, cool-season grasses and legumes.

Management practices may relate to AMF colonization, but they were not affected by management practices related to cutting frequencies. It is also important to note that grass species will form an interaction only if AMF is needed to obtain certain nutrients.

Hernández, Gelley, Borrenpohl, Barker, Bitler and Chiavegato write for Ohio State University Extension.

Read more about:

GrazingYou May Also Like