“Downstate teachers are frontline social workers.”

Chris Merrett doesn’t mince words on rural schools — or rural economies. Yet Merrett, director of the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, is both optimistic about rural Illinois and unrelentingly realistic.

“Underfunding in schools is an issue. The working poor is a real problem. Homelessness and food insecurity is a big issue. A snow day for some kids is a day they go hungry,” Merrett describes.

And comparing rural Illinois today to 10 years ago? “You see more empty storefronts, more uninhabited homes, farmhouses that are no longer being used. You see the impact of population decline,” he says.

MAIN STREET: Chris Merrett, Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, suggests looking to entrepreneurship and small businesses, and considering a community health approach. “Or in other words, if we can’t grow the population, can we improve the population?” he asks.

It’s a hard description to read, but no doubt one that’s familiar to people in small towns across Illinois. Rural population decline has been obvious to both statisticians and the folks who live there.

As USDA reported in its 2014 Rural America at a Glance summary, population losses have affected nearly two-thirds of nonmetro counties. Those declines — or stagnant growth — happened across all types of rural counties, including those dependent on recreation, manufacturing and agriculture.

Population decline is one of three big macroscale forces affecting rural Illinois, Merrett says. Others include technology, which has reduced the number of farmers and farm labor, and globalization.

That’s the reality. But there’s reason for optimism, Merrett says, even if you can’t attract large employers.

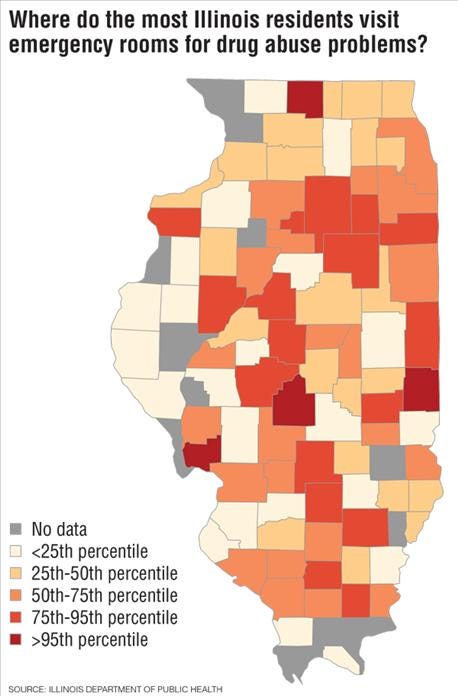

DRUGS: Chris Merrett compares the opioid epidemic — people becoming addicted to prescription pain killers and potentially moving on to heroin — to the methamphetamine epidemic of 15 years ago. “Opioid abuse is affecting a broader portion of society than methamphetamine use did. Yes, there were middle-class people using meth, and while it was significant and serious, it didn’t affect the working class the way opioid use does. Plus, it’s compounded by workplace injury.” This map shows the frequency with which people in each county visit the emergency room for drug abuse and overdose.

Consider North Dakota, where fracking has brought an actual population boom to the state. It’s not likely to happen very often, and certainly not in rural Illinois. Ethanol and wind energy bring a few jobs to an area, but they’re not going to double the population of a rural county. Perhaps, says Merrett, we need to look to entrepreneurship and small businesses and consider a community health approach.

“Or in other words, if we can’t grow the population, can we improve the population?” he asks.

In a lot of cases, that comes down to both education and behavioral health — a fancy term for substance abuse. Or as Merrett puts it, “We see preventable things going on that contribute to diminished quality of life.”

What can farmers do?

Merrett says the first step is to look at public school funding. Referencing the map showing Advanced Placement classes available throughout the state (below), he says we should want our kids to be as competitive as urban kids.

“You want them to have the skill set to do that and be as competitive as kids in Chicago. Clearly by the AP map, they’re not,” he says.

AP WHAT? This map reveals on a district-by-district basis where students are participating in Advanced Placement, or AP, classes. Red districts indicate fewer than 1% of 12th graders are in AP classes — because no AP classes are offered. In green districts, more than a third of the 12th graders take AP classes. (Source: National Center for Education Statistics)

Merrett blames Illinois’ property tax-dependent system. “We need a more equalized funding system that allows rural schools to compete with Chicago. And it seems to me a farmer would be interested in having an education system that’s not property-tax dependent,” he observes.

Education trickles down to economic activity: A better education system helps attract more employment opportunities, and employment results in better quality of life.

The good news is that in June, Gov. Bruce Rauner convened the 25-member Illinois School Funding Reform Commission to make recommendations on revising the current school funding formula to the General Assembly. And he set a deadline: Feb. 1.

In addition to education, farmers should be concerned about public health, Merrett recommends. Ask how your county manages rural health issues. To U.S. Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack’s point, are there addiction recovery services available? Is there access to quality health care? Can a small town teleconnect to a pharmacist to keep a pharmacy in town?

Merrett believes there are often foundations to revitalize a community, if the community can be realistic in its expectations. Or in other words, you probably won’t recruit a Walmart distribution center, he says. But the larger farm community can have an impact.

“Farmers are a huge and integral part of the rural landscape,” Merrett concludes, “and they’re a vital part of the foundation of rural America.”

Read about one innovative program that is working to revitalize rural communities.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like