This year corn farmers in Missouri, particularly in the northeast region of the state, found stunted and uneven cornfields; some plants featured hues of purple. The diagnosis — fallow syndrome.

Fallow syndrome got its name from cropping systems in the dry Plains states, where field routinely benefited from the additional soil moisture available after the previous year had been summer-fallowed.

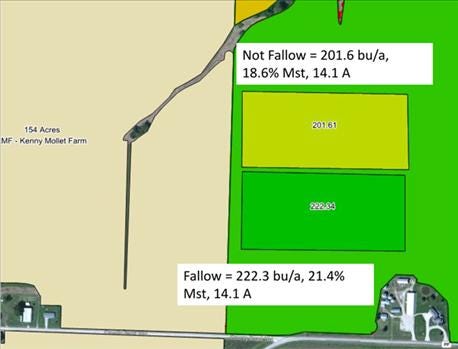

YIELD DIFFERENCE: This summer Jordan Epperson (left), his father, Jim (middle), and University of Missouri grains specialist Greg Luce inspected a cornfield affected by fallow syndrome. At harvest, the Epperson family found a 20-bushel yield difference in corn planted on fallow ground vs. nonfallow.

Fallow syndrome is a result of population reduction of a particular fungus (vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizae, or VAM), due to no plants growing in that field the previous year. It assists the roots in the uptake of phosphorus and zinc. Plants like soybean and some legumes will hold the mycorrhizae in place for the following year. However, the absence of these plants creates a nutrient deficiency problem for the corn.

That was the case at the Epperson family farm in Audrain County. Jordan Epperson purchased the new farm last year. Roughly 50 acres of it went unplanted due to the wet weather conditions in 2015. However, the former owner managed to plant a portion of that same field to soybeans.

In the spring, where the soybeans were planted, the corn performed well. However, the portion of the field that lay barren was not measuring up. The corn had a stunted growth pattern — at least a foot difference in height.

At the time, Epperson was not sure what to expect of yields. It was a matter of wait and see.

Shocked at harvest

With the yield map in hand, it was easy to distinguish yields of the fallow and the nonfallow portions of the field. But it was nothing like Epperson imagined.

DISTINCT LINE: An aerial view from a drone photo shows a distinct line in the field where corn acres were planted into the fallow field. The stunted growth can be seen from the sky.

The area of the field that suffered from fallow syndrome corn actually averaged 20 bushels better than the nonfallow end of the field. Epperson did not manage this area any differently than his other acres. "I think it came to catching later rains," he says.

Greg Luce, University of Missouri Extension grain crops specialist and research director for Missouri Soybean Association, agrees that weather played a huge role in yields. He assessed the Eppersons' corn earlier in the spring and came to the diagnosis of fallow syndrome. And like Epperson, he was surprised at the yield difference.

"It was an interesting thing that occurred with his field and others like it," Luce says. "I really think we had such great growing conditions in August and September that the delay in that [fallow] crop early on was caught up later.

"You don't want your corn to be stunted early on," he adds, "but in this case, it did just fine — and in some cases, like Jordan's, it did a little better than the other."

FROM THE MAP: Jordan Epperson could tell there was a difference from the yield maps.

ODD RESULTS: Pioneer agronomist Nick Monnig put together a map to show the difference in yield.

The results also caught Pioneer field agronomist Nick Monnig off guard

He agrees that rain played a role in fallow-acre corn yields, but adds that wind impacted the nonfallow acres. "The other side of the field was taller and much farther along in the growing season when the winds hit the area," Monnig recalls. "There was some lodging that went on in that field."

Lessons learned

So what did this year of fallow syndrome in corn teach Missouri farmers?

"Not a thing," Monnig says.

"If it happened again, it may work out," according to Epperson.

"I think one thing we learned is that early-season conditions do not always correlate to final yield. In this case, excellent growing conditions late in the season were most beneficial to the corn that appeared set back this spring. Corn is very resilient," Luce adds.

All three agree that if the weather had turned dry during late summer, it might have been a very different story. The corn planted into the fallow field, without moisture, may not have been able to overcome the stunted growth pattern, Monnig says. But this year, the timely rains helped the Epperson family have an unexpected corn harvest after experiencing fallow syndrome.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like