R.P. Cooke says in the southern part of the fescue belt the better you manage grazing the tougher it gets ... at least for a while.

The Sparta, Tennessee, grazier says the benefits that accrue from good grazing management and full recovery of grass before re-grazing also bring with them a new set of problems. Perhaps it's what one might expect, considering the good-grass/bad-grass nature of fescue.

Consider for example, the extension of the grazing season and decrease in dormant season which all good graziers experience. With fescue it means your cattle will ingest the endophyte's toxins many more months per year, without a break. Obviously a problem.

Long recovery: Cooke mostly grass-finishes Jersey steers on his operation and says nearly all his grazing runs about 90,000 pounds stock density and has recovery or three or more months.

Add to that the high ambient temperatures and high humidity of the southern climes and you've got more months of fescue toxicity problem.

Eliminate the summer "drought" season continuous grazers experience every year, replace it with higher soil organic moisture, denser, more lush green fescue, and you've got even more fescue toxicosis, Cooke says.

Over the years he has brought his soil organic matter up from 1% or so to about 5% and he grows grass -- fescue at least -- pretty much 12 months of the year. Cooke says he has been "hay free" for 10 years now and he grazes cattle the year long.

Next, add to the list of problems from the fact fescue is a cool-season forage and often out of balance in protein (nitrogen) to the amount of energy, says the retired veterinarian. This puts excess nitrogen in the bloodstream of the cattle, which acts as a mild nitrate poisoning and produces many of the same symptoms as fescue toxicosis.

Just about right: This paddock has mostly warm-season grasses and is exactly what Cooke tries to manage for, since warm-season grasses tend to have a better ratio of energy to protein.

"High-protein, low-energy grasses lead to high ammonia formation in the rumen," Cooke says. "The ammonia is absorbed and leads to a high pH in the animal, or alkalosis."

However, there are solutions and a way forward, he says.

Cooke has actually written his methods into a series of articles about his 30 years improving his land with grazing and dealing with the fescue issues as the evolve. He calls it the "Highway 40 Blues" and says these southern fescue problems persist along a corridor which runs up to 100 miles either side of Interstate 40 from eastern Oklahoma to the Atlantic Ocean.

Cooke nearly every year sponsors grazing management meetings, sometimes featuring his friend Gordon Hazard, author of the book Thoughts And Advice From An Old Cattleman, and a man made relatively famous in grazing circles by books and articles written about him by others. By way of those meetings and a steady diet of cell phone conversations, Cooke has come to know and share knowledge with grass producers and especially with fescue junkies like himself across the nation.

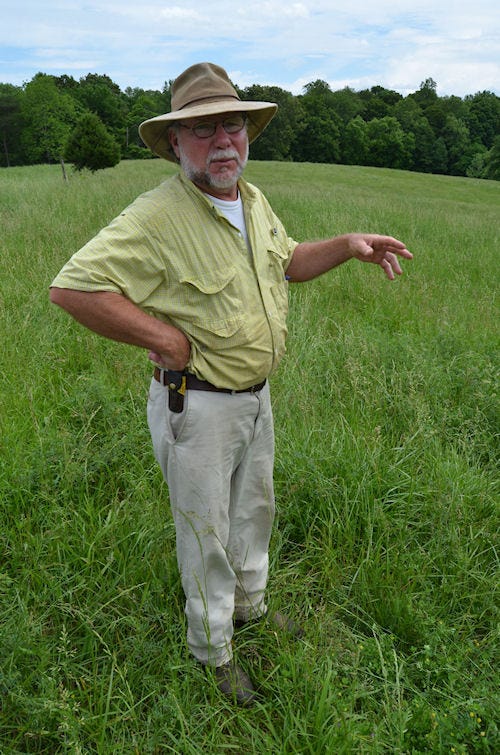

Dilution solution: Tennessee grazier R.P. Cooke says big fescue is fine if you can beat it back to 35% or 50% of your grass stand in favor of warm-season grasses.

Fundamentally, Cooke says to the answers lie in "diluting" that wonderful stand of fescue you've developed with as much warm-season grasses as you can, bringing in the best adapted cattle you can find, eliminating nitrogen fertilizer from your managerial repertoire and supplement key minerals and some energy as affordable and/or effective.

R.P. Cooke's 16 tips for Kentucky 31 fescue management

R.P. Cooke has a list of things he's learned about dealing with that "better" fescue Southern graziers get from planned grazing. Here they are:

1. Dilution is the key to pollution. Fescue needs to make up no more than 35% of the pasture component.

2. Monitor roadsides and manage your pastures to try to reproduce what grows there.

3. Provide forage complete recovery after grazing to increase diversity. The more species the better: grasses, legumes, herbs and forbs.

4. For shade, grow protected small and deep groves of trees. One-wire electric fences will protect these from overuse and trampling when they're not needed.

5. Plan grazing that delivers high animal impact for short periods in the spring. Make a little mud. This sets back the fescue and gives other plants a chance.

6. In high rainfall areas above 35 inches annual average, soil health, plant health and animal health require regular small applications of lime.

7. Supplement cattle with a rumen microbe stimulant, energy, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, lots of loose salt, and trace minerals. Clean water is a necessity.

8. Eliminate chemical nitrogen if your fescue is dominating your pasture and "blowing up" in the spring.

9. Consider "overgrazing" areas of heavy fescue growth in early-spring by allowing cattle a longer grazing period or a second grazing period. Do so before the warm-season plants you want begin to emerge.

10. Learn to plan, manage, and graze for an increase of the perennial tall warm-season (C4) grasses that grow in your area.

11. Mow the fescue dominant areas for hay every third year. "I always lose money when we mow hay but it does set the fescue back," Cooke says. It also decreases soil health and development.

12. Consider applying four to six ounces per acre application of paraquat in the late March, April, or early May on very dense areas to send the fescue dormant. Paraquat is dangerous but short-lived and seems to hurt fescue and other C3 grasses worse than it does other plants.

13. Do not bet the farm on novel endophyte fescue varieties.

14. Get adapted cattle genetics. Sell cows that cannot perform in your environment. Do a lot of looking before purchasing. Get out of the truck and look at the grass, the cattle and the feed program. If the seller is feeding hay for more than 60 days per year, do not buy. If there is not a lot of grass, do not buy. If the cows weigh over 1,000 pounds, do not buy. Whenever in doubt, do some more looking.

15. Attend pasture walks in the fescue belt at different times of the year.

Take notes, ask questions, think, learn and take action.

16. Do not spend excess money on silver bullets. They do not exist.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like