Land farmed in row crops isn’t necessarily the best use. Some farmers decide that especially for land along streams that floods frequently, there may be better options. When the Farm Service Agency, part of USDA, offers cost-share incentives for practices and payment for acres enrolled in certain programs, it can be the catalyst some need to convert land to uses other than farming, at least during the life of the USDA program.

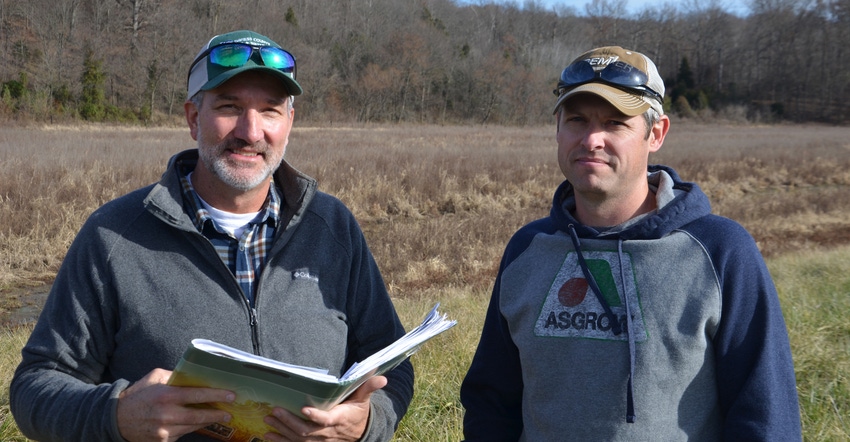

Kyle Turpin and other family members who own land with him recently made that decision for ground along the Lost River in Martin County, Ind. TS Acres LLC — consisting of Kyle; his wife, Bobbi; and her brother Jason Self, enrolled the land in the Conservation Reserve Program. The Natural Resources Conservation Service provides technical assistance for landowners in CRP.

Making changes

It wasn’t as easy a decision as it might seem. For the land to qualify, they had to agree to complete several conservation practices. In return, they received cost share for the practices and now receive rental payments while the land is in CRP.

Mark Cambron, district conservationist for NRCS in Martin and Daviess counties, assisted Turpin and his partners in deciding how to best use the property and which conservation structures to install.

Trevor Shepard, engineer for the Indiana NRCS Southwest Technical Team, also assisted in designing structures and practices for the site.

“One practice they installed was a water control structure, which allows them to regulate the water level on one section of the property,” Cambron says. “The land can be used for hunting, so Turpin allows water to cover that area part of the year.”

Turpin and his family enjoy duck hunting. “There were already ducks in the area, but this provides more habitat for them,” he explains. While the property is still in the early stages of conversion, he was able to hunt ducks during the season this year.

A different area of the land is devoted to pollinator habitat, including warm-season grasses and forbs. That area can be mowed annually to control noxious weeds. Mowing is limited to after the nesting season for wildlife.

Environmental benefits

Chris Lee, Southwest Technical Team leader, steps back and takes a big-picture look at the project. “It’s important because this is a very sensitive ecosystem,” he says. “The Lost River spends much of its time underground in caves. That affects the type of species which are in this particular river.”

The Lost River surfaces in Orange County, Ind., and flows aboveground, emptying into the East Fork of the White River in Martin County, Ind., Lee explains. Restoring a wetland and planting other land to grasses and forbs provides far less chance for sending nutrients or sediment into the stream than it if were still farmed.

Turpin and his family practice no-till and use cover crops on other land. Members of the grain cropping operation include Kyle’s dad, Drexel, and his brother J.D.

Even using conservation practices on this land, flooding often interfered, Turpin notes. He believes this is the best use of this land today.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like